|

Resources from a Messianic perspective |

|

IT'S STILL THE PROMISED LAND Download a PDF version of this article

In the midst of public protests against the nation of Israel, a common slogan that is chanted and depicted on signs is “From the river to the sea Palestine will be free.” It is a direct reference to the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, which makes it a proclamation of the desired boundaries of a future state of Palestine. That entire territory from the Jordan to the Mediterranean would encompasses the entire land of Israel. So, the real meaning of this phrase is a call for the elimination of the state of Israel, which would require the displacement and genocide of the Jewish people who dwell there. This anti-Israel slogan is in direct conflict but with the words that God as declared, as recorded in the Bible. For it is written in Scripture that a series of truths are given regarding the land from the river to the sea. God has the right to give any land to anyone As Psalm 24:1 declares: “The earth is the LORD'S, and all it contains, the world, and those who dwell in it.” Ironically, some Christians today either ignore or redefine the word “all” because they do not apply it to the land of Israel. They do the same with a related verse in Psalm 115:3 that reads: “Our God is in the heavens; He does whatever He pleases.” God’s sovereignty is further demonstrated by declaring: “I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy” (Ex 33:19; Rom 9:15). Much more could be said about this subject, but suffice it to say that the Bible makes it clear that Adonai truly is Lord over the universe, and He has both the right and the power to grant possession of any part of His land to anyone that He chooses. God sovereignly gave the land of Canaan A specific promissory aspect of the Abrahamic Covenant is the Promised Land. The boundaries of this land are frequently defined in the Bible, often in precise detail. The first reference to the land followed God's promise in Genesis 12 that a great nation would come from Abram (whose name was later changed to Abraham in Genesis 17:5), which would ultimately be the nation of Israel. Abram then began a journey into the land of Canaan, and God told him:

The extent of the Promised Land, therefore, was based on everywhere that Abraham could see as he walked during his journey. Back in chapter 11 we are told that He was originally from the city of Ur, which is in the south of modern-day Iraq. But he had relocated to Haran, which is now just over the border from Iraq into Turkey, and a short distance northeast of the Euphrates River. That is where God declared the Abrahamic Covenant to him, and it is where he began his journey, walking throughout the land of Canaan and seeing the lands that would establish the boundaries of the future Promised Land.  He also made a diversion to Egypt to escape a famine in the land of Canaan. Without that famine, it is likely that he would have stayed more centrally in the land of Canaan and wouldn't have ventured all the way across the Negev and Sinai wilderness areas. But by going to Egypt, it meant seeing with his own eyes the western-most boundary of the land of Canaan, thus gaining entitlement to the full territory. In Genesis 15, God finalized the covenant by declaring the specific boundaries allotted for the nation that would later arise from Abram:

It is generally believed that the "river of Egypt" is a reference to the Wadi El Arish a river valley that separates Egypt from the land of Canaan. Later, in Exodus 23:31, God made it clear that the southern boundary extended all the way to the Red Sea. The northeastern border of the Promised Land is the headwaters of the Euphrates River where Abram began his journey. Then in Genesis 15:19-20, God confirmed the extent of the rest of the territory by describing all of the Canaanite tribal lands that He was giving to Israel (each of these lands have been identified, with the exception of the Kenizzites who possibly lived on the border of modern-day Saudi Arabia).  As the book of Joshua begins, God made it clear that the Promised Land extended to what is now called the Mediterranean Sea:

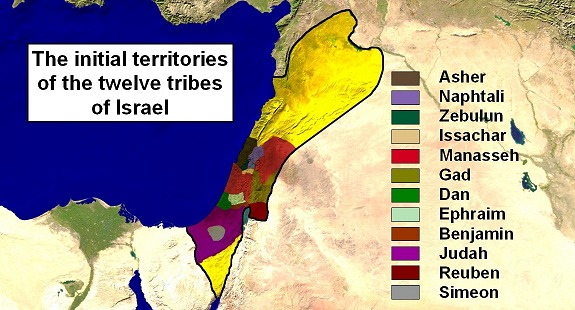

Therefore, by taking into account where Abram walked on his journey, where the Canaanite tribes were located, and the specified water boundaries, we are given a rather complete sense of the extent of the land that God promised to the descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.  What happened next, however, was not the acquisition of the entirety of that mandate. In Numbers 34, God gave instructions regarding the extent of the Promised Land that the Israelites were to claim initially, and He gave very detailed boundaries for them to follow. Later, when they actually entered the land, the twelve tribes of Israel were assigned specific territories within those boundaries. In fact the description is so precise that seven full chapters of Joshua (nearly one-third of the book) are dedicated to those boundaries, which makes it clear that they didn't dwell on the full Promised Land.  Under David and Solomon the kingdom of Israel was extended to all of the borders originally designated by God (1 Ki 8:65), with two exceptions. Shortly after the tribe of Judah entered the Promised Land in the south and took possession of the region of Gaza, that coastal strip was invaded by the Philistines, who came by ships, and Judah lost that territory. Afterward it was never taken back by Judah or later by the kingdom of Israel under David and Solomon. Likewise, the northern coastal region inhabited by the Phoenicians was never taken. So while David and Solomon came very close, there has never been a time when Israel possessed the entire Promised Land.  As time passed, the borders began shrinking, with the dividing of the kingdom, and then losing territory by being conquered by Assyria and Babylon, followed by Greece and Rome. After the failed Bar Kokhba rebellion against Rome in 135 A.D., Jewish possession of the Promised Land came to a complete end. All of it had been lost, even though the Jewish people retained the divinely given legal right to the land. But the promise was never forgotten. Jewish people scattered around the world maintained hope for a restoration of their homeland. That dream passed from generation to generation, century after century. In the year 1516, the ancient land of Israel became part of the Ottoman Empire, which would last for 400 years. In spite of their dominance, the Ottomans made a strategic error when they aligned with Germany in 1914 during the First World War. Two years later, in 1916, anticipating a victory in the war, British and French leaders made an agreement how to administer the defeated Ottoman territory. Named after the primary negotiators of the two countries, the Sykes-Picot Agreement established official policy that called for France to control the northern part of the empire, and the British to control the south. They could establish states within their respective areas however they saw fit. They also intended for the territory of ancient Israel to have an international administration.  At that time, Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, had been a strong advocate for the Jewish people, especially those in Russia who had suffered in the physical violence of pogroms in that country. Balfour saw the need for finding a place where Jews could live in safety, and he was friendly toward those in the Jewish Zionist movement who believed the only suitable place for that home was in the land of their forefathers. The potential demise of the Ottoman Empire in the midst of WW1 presented such an opportunity. In 1917, one year after the Sykes-Picot Agreement, Balfour issued a letter to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, that expressed the official position of the government in what became known as the Balfour Declaration:

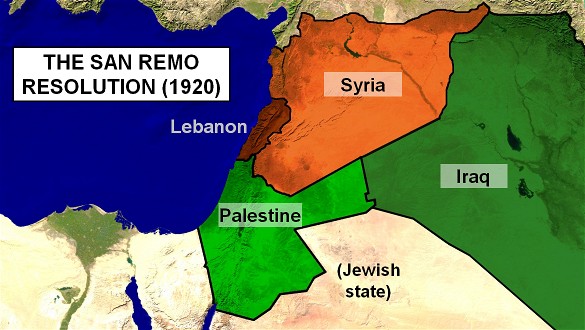

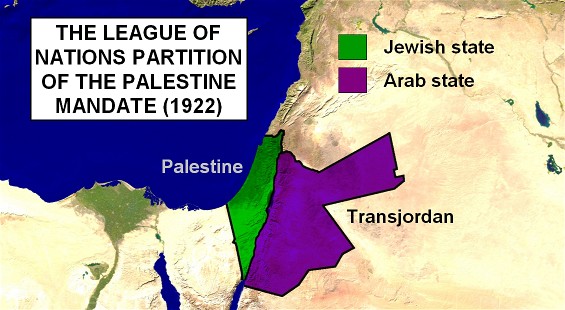

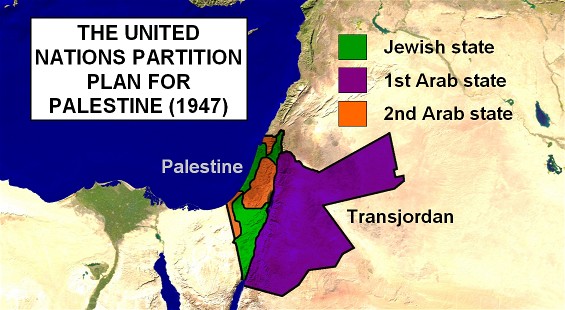

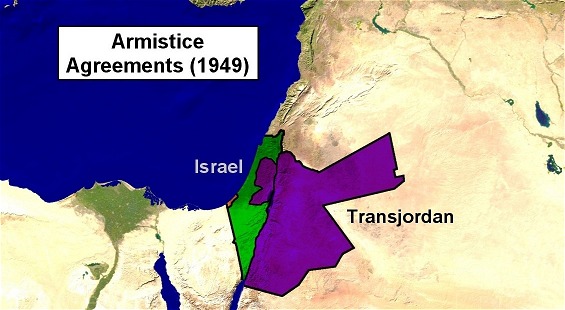

In 1920, two years after the war ended, representatives of the victorious allied nations met in San Remo, Italy. They adopted the position of the Balfour Declaration and incorporated it into the official policy for the creation of states from the fallen Ottoman Empire. In keeping with the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, the San Remo Resolution gave France a mandate for the creation of Syria and Lebanon. And Britain received a mandate for the creation of Iraq and Palestine, with the latter being the "national home for the Jewish people" set forth in the Balfour Declaration. The borders of the Jewish state of Palestine were to encompass much of the biblical Promised Land.  But objections arose over the prospects of a Jewish state being restored on the land of their forefathers. Wanting to appease the Arab population in the region who intensely opposed a Jewish homeland, British leaders began backing off their original intentions. So when the League of Nations ratified the Palestine Mandate in 1922, instead of a Jewish state extending close to the biblical Promised Land according to the San Remo Resolution, it was partitioned into two states, a Jewish state called Palestine on the west bank of the Jordan River, and an Arab state called Transjordan on the east bank of the river.  The dividing of the land did not stop there, however. The creation of the new states of Palestine and Transjordan were put on hold for over two decades. During that time, a series of commissions—Peel, Woodhead, Morrison-Grady, UNSCOP—discussed how the remaining portion of the Palestine Mandate could be divided again, with a second Arab state being taken from the Jewish homeland. Eventually, in 1947, the newly formed United Nations approved a plan in which Jews could have a patchwork state that only included the eastern Galilee, the Jezreel Valley, the northern Mediterranean coast, and the Negev. That meant receiving 13% of the original Jewish homeland that had been determined 25 years earlier.  Remarkably the Jewish leaders approved the plan, even though it was both a small portion of the land originally intended for a Jewish homeland, as well as a token portion of the actual Promised Land in the Bible (shown below).  Arab leaders, on the other hand, rejected the partition plan. The reality is that the Arab world at that time did not want a single inch of land to be a Jewish homeland. And in light of the words and actions that are evident today, it is not difficult to see how that position is still widely held. In any event, when Israel received its independence in 1948 on those minimal lands, the new nation was immediately invaded by the surrounding Arab countries, who sought to take away every last plot of ground designated for Jews. But that move ended in defeat, and Israel was actually able to regain some of the land that had been taken away by the politicians who went back on their commitment years before. Those borders were ratified in a series of armistice agreements with each of the invading Arab nations the following year.  In the midst of Israel's War for Independence, Transjordan invaded and gained control of the West Bank of the Jordan River. So in reality, that nation, which was renamed Jordan in 1949, was the one who occupied Palestine. The West Bank was never part of its legal mandate. But, as we have seen, when the territory was first designated in modern times, the West Bank was to be included in the Jewish state, which was called Palestine at that time. The chronicle of shifting borders has continued ever since, including Israel gaining control of the West Bank when it was attacked again by Arab nations in 1967. And Israel has subsequently relinquished part of that land, with international calls for more changes yet to come. But much of the confusion evident today is that the world neglects all of the legal commitments made prior to 1948, leaving the assumption that the present conflict is entirely a matter of Israel controlling "occupied land." It is clearly not that simple. We are able, however, to identify several additonal biblical principles that relate to the Promised Land. The entitlement of the Promised Land was given permanently As part of the Abrahamic Covenant, the land promise shares the overall nature of the covenant, most notably, its permanence. God declared:

This sense of permanence is magnified in the 105th Psalm:

This passage brings out the permanence of the covenant four ways:

Altogether the land aspect of the Abrahamic Covenant is described in such a way in Scripture that it conveys the sense of a promise that remains intact throughout all time. God's granting of the Promised Land is a binding legal agreement The terminology often associated with the Promised Land is consistent with what is found in wills. In these documents, heirs and beneficiaries are identified, and the owner of the estate is free to limit who those heirs may be. Wills describe the inheritance they specifically receive, and the estate does not have to be equally divided. In other words, God is free to bless human beings in different ways and He calls us to different purposes while dwelling on this earth. And the same is true regarding land, so that no amount of jealousy and protesting will alter God's stated promise. Wills also remain in effect until they are rescinded or replaced with a new one. There are a number of arguments people use to claim that God has rescinded His will regarding the land. But they can't cite a direct statement in Scripture because none exist. In fact, the opposite is true because Paul has declared in Romans 10:1 that God has not rejected His people, referring to Israel. Opponents typically argue there is nothing specifically said about the Promised Land in the New Testament, so that must mean that God has changed His mind. However, that is based on a sense that there are two distinct books of the Old Testament and New Testament, and if something is not mentioned in the latter book, it is no longer relevant. But when Paul writes: "All Scripture is inspired by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for training in righteousness" (2 Tim 3:16), he was referring to the Tanakh (Old Testament) because the New Testament had not been written yet, although his words would apply forward to those Scriptures as well. The point is that in the Bible, once a principle is established by God, He doesn't abandon it, but the underlying meaning persists throughout time, at times with enhancements made to the way it is accomplished. That is, these principles tend to be deepened without jettisoning the original intent. For example, the Torah (Law) (Jesus) instructed people to "love your neighbor as yourself (Lev 19:18). Later, Yeshua taught that you neighbor included your enemies, not just people you liked (Mat 5:44). But that doesn't mean you weren't obligated to stop loving the people you like as well. Enemies, according His teaching, are just added to our friends. Such is also the case with the inheritance of God's heirs. It is clear that God has added Gentile believers to His will, promising an eternal inheritance to all who believe in Yeshua (Eph 1:5-18). But He never annulled the provision of His will regarding the entitlement of a specific territory to specific heirs while living on this present earth. One does not preclude the other, just as it is true concerning loving your neighbor and many other biblical matters that are deepened without abandoning the underlying principle. The present circumstances are not an indication of the reality of the land promise of the Abrahamic Covenant There has never been a time in history when God's promise regarding the land has been completely fulfilled. According to the expressed will of the Creator of the Universe, Abraham was the rightful owner of the full measure of the land that he saw while he walked. But he was never recognized by the people dwelling on those lands as the holder of the deed. The same was true for Abraham's heir, Isaac, and his heir, Jacob. Certainly that was the case for the next four centuries while their descendants lived enslaved in Egypt. Surely the inhabitants of Canaan had no clue that the land they were living on at that time actually did not belong to them by divine declaration. When the Jewish people were taken away to Babylon, their captors did not recognize their right to the land. And the same was true for the Romans in the days of Yeshua. And it has been the case in every generation since then. The point is that you can't look at the circumstances of the day and decide what the ultimate reality is. The complete fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham and his descendants may not be realized until Yeshua returns to this earth and inaugurates His Messianic kingdom that will last a thousand years. But the present situation in the world does not negate that certainty whatsoever. Our response to God's stated will is an indicator of From the moment that Adam and Eve sinned in the Garden of Eden, humanity has disputed God’s total sovereignty over our lives. It has been a continual battle regarding who has the final world in what we say and do. It is somewhat easy to do what God instructs us to do when we want to do it anyway. The real test comes when issues of fairness, jealousy and coveting come into play. Surely that is the case when it comes to the Promised Land. As we have seen, God has stated His terms. The only question is—can we abide by them? The answer to that question enables God to know if we have truly made Him Lord over our lives, or if our own will reigns supreme. The enemies of Israel have made their answer clear. The way that they are acting is described perfectly in Psalm 83, which describes the enemies of Adonai making plans against His people [Israel] and conspiring together to “wipe them out as a nation so that the name of Israel will be remembered no more" and to possess for themselves “the pastures of God." That is precisely what they are intending with the words, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” So, their words are more than a political statement, it is a declaration of rejecting the lordship of Adonai, the true and living God. Now, there is much more that needs to be said, including how God declares in Joel 3:2 that He opposes nations dividing His land and taking it away from His covenant people. And we also know that, in multiple passages, God calls His covenant people to welcome into their midst and to care for strangers who are committed to peace. Taken together, that means the Bible calls for a one state solution with Jews and Arabs living together in harmony. At this moment, those prospects seem impossible from a human perspective. But that is what God mandates in the Bible and it will become a reality in the millennial kingdom to come because Yeshua will make it happen. So that should guide our thinking in light of the world’s continual demands for dividing the land today. It all comes down to submitting to the Lord of this universe. And even if you do believe in the God of the Bible, are you willing to let Him exercise His sovereign will over this earth? The key issue of the day is this—if you disregard God’s stated will and align with those who are claiming His land, according to the Bible, you are in rebellion against God because it elevates personal opinion over His authority. Today is the day to let Adonai be Lord over your life in every way. Let us acknowledge that God never forgets the covenant He made with Abraham and His descendants, and neither should we. For Adonai is still a promise keeping God. So, just as believers in Yeshua have the secure promise and inheritance of everlasting life, Israel retains the God-given inheritance of the Promised Land from the river to the sea, just as He first declared on that day long ago to Abraham. May we all recognize that we can count on God always to do exactly what He has promised, regardless of the circumstances of this rebellious world. Dr. Galen Peterson |